Part 1 – Why It’s Just the Worst.

Part 2 – How I Started as a Streamer but then Saw the Light

Now that I’ve shared the importance of destreaming as an act of anti-racism and anti-oppression along with a personal journey to get to that thinking, here comes the part that most people probably just wanted me to fast-forward to:

How do teachers successfully teach an inclusive destreamed class???

Simple. It involves a battery, chewing gum, and a coat hanger.

Outdated ’80s references aside, effective teaching in a destreamed class can involve some Macgyver-like ingenuity with already-existent pedagogical tools. Because equity-centred teaching involves knowing the learners in a classroom, there is no prescribed set of instructions that I can share that will necessarily work in all environments. However, I will introduce approaches that are rooted in the discourse of inclusion, anti-oppression and destreaming. This is by no means an exhaustive guide, but I will say this is a good place to begin gathering research-informed ideas and start a professional inquiry on destreaming.

One last note: my teaching background is in secondary school math, so many of my examples will come from that angle. I also work with amazing colleagues who have destreamed English classes effectively so I will also draw examples from their work.

Be a culturally responsive teacher.

Culturally responsive educators have these mindset characteristics:

To be an effective teacher transitioning into a destreamed environment, one has to realize that they are an active change agent in dismantling a harmful structure. They understand that not every student has had a privileged educational experience and seek to enhance equity in their learning space. When a teacher encounters challenges in their classroom, this goal serves as fuel to persevere.

No teacher will ever admit not to hold high expectations for students, but there are ways low expectations manifest in classrooms. Simply being satisfied that a student attends class but disengages all day because they face challenging life circumstances is one such example. Excluding some students from higher-level learning opportunities because “they need to sure up the basics first” is another example. Opportunities for critical thinking and problem solving are even more important for students that need to learn those skills. Peter Liljedahl’s Thinking Classrooms framework provides both the push and support that struggling learners need to help improve their thinking skills. Holding high expectations means providing the best curriculum, programming, and pedagogy for everyone, while expecting success from all students.

A successful teacher in an inclusive class also understands that students learn best by building on prior knowledge and constructing their own understanding. Below is an example of a series of questions that teaches students how to simplify algebraic expressions through sense-making. This not only validates the knowledge with which students bring to class, but it also promotes enduring understanding.

Finally, a destreamed class should provide opportunities for students to see themselves and issues that matter to them reflected in their learning. For instance, students can learn mathematics through relevant issues of social justice. MathThatMatters and High School Mathematics Lessons to Explore, Understand, and Respond to Social Injustice are great books to spark ideas for K-12 teachers wanting ways to infuse issues such as climate change and systemic racism into their math blocks. To ensure students have access to reading materials that reflect their identities and lived experiences, let them help with choosing the books that you or your school purchases for library collections.

Focus on inclusion through Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

Effective destreaming means thinking about inclusion, which involves reimagining learning spaces that are free of barriers to student participation, rather than fitting people into an existing space with visible and invisible barriers. Student variability of all kinds already exists in every classroom; how educators anticipate and respond to those differences will be even more important in a destreamed setting. Here are a few simple examples of what I have done to make my classes more inclusive, and where these examples fit along the Universal Design for Learning framework:

Engagement

- Including student interests (ones that I have uncovered through having conversations) into math lessons.

- Designing assessments that are short enough in length so that “extra time” fits into regular class time, and all students are entitled to that time, while also providing an independent activity for those that finish quickly.

- Providing any homework I have planned at the beginning of class so students that learn quickly can begin practicing while I provide further explanations to those that need them.

- Making available classroom tools and anchor charts and posting supplemental videos online.

Representation

- Using visual (e.g. graphs and diagrams) and concrete representations (e.g. linking cubes, algebra tiles) as much as possible to illustrate abstract concepts.

- Encouraging multiple ways for students to present solutions and having students make connections between solutions.

Action and Expression

- Solving math problems on vertical surfaces or at tables, in groups or individually.

- Leveraging computer algebra systems to serve as assistive technology for students that have significant learning gaps in computational skills, but all students learn how to use them and can access them at all times in the classroom.

Better yet, combining the principles of UDL and culturally responsive pedagogy gives teachers an even greater base of knowledge about students to effectively plan inclusive learning spaces.

Differentiate instruction to meet particular student needs.

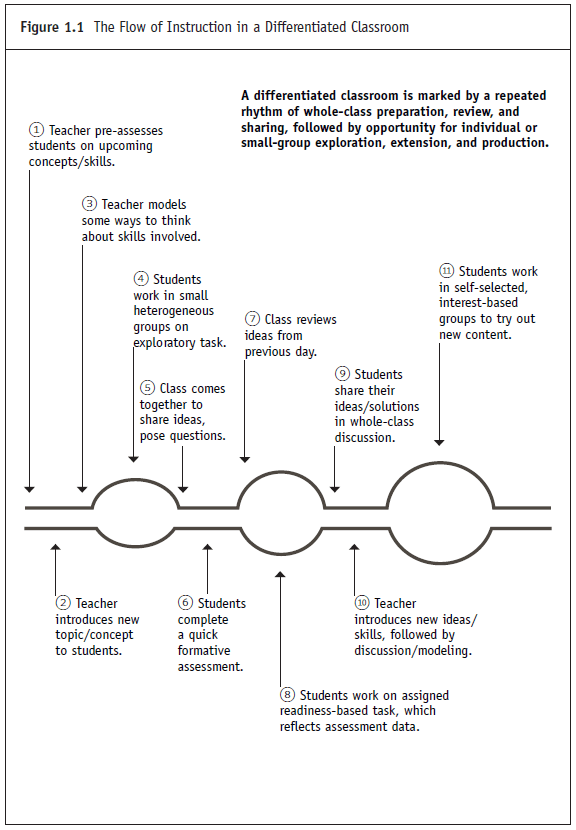

If UDL is about anticipating students’ needs, then differentiated instruction responds to them. When teachers are asked what their greatest concern is about teaching destreamed classes, most will identify the challenge of meeting the wide range of student readiness. Designing differentiated learning opportunities to meet students at their readiness level while creating a pathway for growth is a key element in any inclusive class.

A prevailing myth of differentiated instruction is that a teacher must make individual lesson plans for each student or a group of students. In reality, differentiation involves an ebb and flow between whole-class and small-group/individual activities, informed by assessment.

In my math class, I typically introduce a topic, have students in random groups try an open task with multiple entry points while I observe and guide, we discuss specific solutions as a group, and I consolidate the learning for the day. Mixed in there could be parallel tasks where I provide choice in questions of varied complexity but which focus on the same big idea. If I notice students struggling after the consolidation, I work individually or with a small group to try to quickly address misconceptions.

In Grade 9 English classes where students’ reading levels can range from Grade 1 to 12, studying a whole-class novel may not be the most effective approach. Teachers in destreamed English classes have begun to employ differentiated book clubs based on the work of Penny Kittle that allow students choice to access texts at their reading levels and meet their varying interests. Students still demonstrate proficiency in the overall expectations of the English curriculum with their chosen texts. Finally, more reading begets better reading, so students that are engaged in their choice of books greatly increase their reading volume and thus improve their skills exponentially.

Ensure your assessment practices are fair and equitable.

As teachers, we must inevitably place a judgement on how well students have achieved the overall expectations of subjects. Ensuring that assessment practices are fair and equitable must be a focus for any destreaming program to be successful. Let’s break down those two aspects:

Fair: Ontario’s evaluation system is mandated to be criterion-referenced, meaning that students are judged in reference to levels of the achievement chart that are standard across the province. This is in contrast to norm-referenced evaluation, which measures students to each other. The reality in many spaces across Ontario is that norm-referencing still prevails to some degree — Applied classes may have a lower bar set because students in those classes tend to be underachieving, while Academic classes may set the bar unnecessarily high as a means to invoke challenge. I do not for a moment suggest that the quality, richness, and “rigour” of learning opportunities should decrease in destreamed classes, but simply that the standard for judgements for reporting purposes must be reset so as to fulfill the criterion-referenced mandate of Ontario’s evaluation system.

For example, secondary students that show limited knowledge of content and use thinking, communication and application skills with limited effectiveness are still entitled to pass a course with a mark of at least 50%. Although you may not have faith in a mechanic with limited knowledge of cars or trust a surgeon who has demonstrated limited effectiveness, that level of unease is actually what is sufficient for students to accumulate credits and proceed on to the next course. In addition, how teachers assume a struggling student will perform in a subsequent course is not relevant when determining a grade for their current course. Teachers and school teams need to reflect on their assessment practices to ensure they are aligned with policy and are not unnecessarily holding students back from accumulating credits and proceeding on with their schooling.

Equitable: Not all students need to have the same number or types of assessments. Personally, I provide as many opportunities that students want and need to demonstrate the limited understanding they need to pass. I also take into consideration the observations and conversations that I have particularly with struggling students to get a more accurate sense of what they know.

Use pedagogy that’s actually supported by cognitive neuroscience.

Through his work on meta-analyses, education research John Hattie has shown that pretty much anything teachers try has a positive effect on student learning (TVs in the classroom and failing students are some of the rare exceptions). However, some strategies work more effectively than others and have evidence from cognitive neuroscience to back them up. Here are a few strategies that are worth mentioning in the context of destreaming:

Spiralling (or spacing, interleaving) is the practice of revisiting and relearning content after a length of time has passed. Spiralling offers multiple opportunities for the retrieval of knowledge from memory over the course of weeks or months, which helps to strengthen neural connections. I have been experimenting with spiralling in my math class, along with others, with positive results. An added benefit that I have found is that the first spiral consists of surface-level content and connections, which serves as a soft landing for Grade 9 students that are coping with a new school environment and entering with varying levels of math understanding.

Dual coding involves combining information in different forms, such as words with pictures, or descriptions of math relationships and graphs. Whenever possible, I incorporate images, diagrams, and graphs and link them to the verbal explanation. With all kinds of multimedia technology at our disposal, this strategy is easily employable. Dual coding and providing visuals and auditory modes is not to be confused with learning styles that has no scientific basis.

Active learning involves engaging in learning tasks rather than passively listening to a lecturer. Thinking through complex tasks involves more neural cross-talk and leads to greater neural connections. Although I would argue all teachers recognize the benefit of having students active during class time, some may still lean towards lectures in response to positive feedback from students. However, a recent Harvard study showed that while students feel they learn better during lectures, they actually learn more effectively when engaged in active learning. Also, with universities increasing their use of active learning approaches, such as the University of Toronto, University of Waterloo, Queen’s University, and Western University, successfully preparing students for post-secondary education necessitates deep learning and engagement.

Have a school-wide intervention strategy.

Even in the most inclusive and differentiated learning space, there may be some students that require additional intensive support to achieve success.

A concern amongst teachers in destreamed classes is a struggling student’s reading ability. By high school, a student should be reading to learn, but what if they still need help learning to read? The Right to Read program that was launched at Runnymede Collegiate Institute in Toronto and since replicated in other schools has shown that targeted one-on-one support for a few weeks can lead to a year’s worth of reading gains or more (here is a TDSB report with methodology, case studies and recommendations).

Schools in the TDSB have also begun to experiment with a transitional math course in the first semester of Grade 9 for students that significant learning gaps. To prevent such a course from being yet another streaming structure, placement should require intentionality and oversight, and all students must also enrol in Academic math for the following semester. The course content differs from school to school, but teachers have highlighted the need to develop students’ number sense in order to best set them up for success in subsequent math courses. Even with a new destreamed math curriculum on the horizon, a transitional course may be still required.

Destreaming the educational system by altering the structure alone will not lead to the desired effects of removing systemic barriers for Black, Indigenous and other marginalized students — in fact, evidence suggests it would likely exacerbate societal inequities. Meaningful pedagogical shifts and intervention supports, backed by human and financial resources, must accompany the structural changes. Effective destreaming is not easy work, and progress may not be linear, but we owe the marginalized youth of Ontario our best collective effort to reset the educational system and bring about real and substantive change.

Kudos to the educators whose work I’ve drawn upon for this post: Kulsoom Anwer, Rachel Cooke, Michelle Defilippis, Stephen Dow, Sean Henderson, Ramon San Vicente, Reshma Somani, Leigh Thornton, Sylvie Webb.

Really enjoyed the article and the practical solid suggestions.

“…based on students’ perceived abilities and identities.” does not address the needs of those who have real, documented, and pervasive learning challenges. Destreaming has done nothing but perpetuate the discrimination in my child’s classroom, and has once again told her that she is incapable of meeting the standard. Destreaming might be a viable solution for the ‘average kid’, but for those with significant learning challenges, it is devastating- to the point of pulling our daughter out of school. You can read more here: https://www.thespec.com/opinion/contributors/2022/11/10/destreaming-perpetuating-discrimination.html

Hi Tracy. Thanks for sharing your story, and I empathize with your daughter’s situation. Some of her experiences should not be happening.

Anti-oppressive change needs to happen at both the system and individual levels. Destreaming assists with the system-level change. You make a valid point that “teachers are not familiar with modifying class work to accommodate students of such a wide range of varying abilities,” and that is the individual aspect of this change.

Generally, teachers are not yet skilled in accommodating a wide range of student readiness because historically, teachers have never had to do so. Prior to destreaming, students who did not fit the mold in an Academic class would simply be placed in a lower-streamed class with fewer opportunities and rates of success. We need staff to learn teaching skills that promote inclusion. That simply would not happen at scale in a segregated high school system. I am familiar with many school boards and their supports, and I know that every board has dedicated staff to assist teachers with making classes more inclusive.

I am a firm believer that systems drive teachers’ behaviours and attitudes. Destreaming classes is one step – an important one – but an important one that sets the conditions for greater improvements in teaching and learning in ways that matter most, ensuring that every student, regardless of race, income, or (dis)ability, can meet their fullest potential. That would never be the case without destreaming.