It’s been almost 10 years since I started my whirlwind destreaming journey. What started as a small initiative with six Toronto District School Board schools serving predominantly Black students to address their overrepresentation in lower-streamed courses eventually transformed into a district-wide mandate. Soon afterwards, the Ontario Ministry of Education began destreaming all Grade 9 courses as an approach to address long-standing systemic discrimination based on race, class, and (dis)ability.

Such a fundamental change in how secondary schools organize children naturally comes with a stage of transition. While many educators are successfully transitioning towards a more differentiated approach to teaching that supports a wider range of student readiness, some educators are not. Staff that are struggling with this transition are reporting a lack of resources and funding towards effectively implementing destreaming. While teachers seem to be “getting by,” I agree that more resources are required for staff to feel more confident and less stressed about meeting students’ needs in inclusive classes.

But, there is a sentiment amongst some educators and community members that destreaming is not working. Staff that are having difficulty meeting diverse learners’ needs are sharing their experiences of students failing classes or having to lower their expectations, which leads to underpreparedness for future learning. I empathize with teachers and school administrators that feel they are not receiving the time, resources, and support they need in order to do their best work. However, to assess the impact of destreaming as a whole, it is critical to examine system-level data to layer on top of our own personal experiences.

That is why I’m sharing a portion of a recent report that I co-wrote, entitled Academic Pathways Strategy: Supporting Students from Kindergarten to Apprenticeship, College, University, and the Workplace. This report, published in September 2024, provides an historical overview of what the TDSB has done with respect to destreaming, a current assessment of destreaming efforts district-wide, and what steps the district will be taking to maintain the highest expectations for students while continuing addressing educational barriers for Indigenous, Black, and disabled students, and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

To read the original report, go to Page 79 of this document (the portion below includes some minor grammar and citation edits and the addition of links).

Academic Pathways Strategy: Supporting Students from Kindergarten to Apprenticeship, College, University, and the Workplace

History of Addressing Academic Streaming in the TDSB

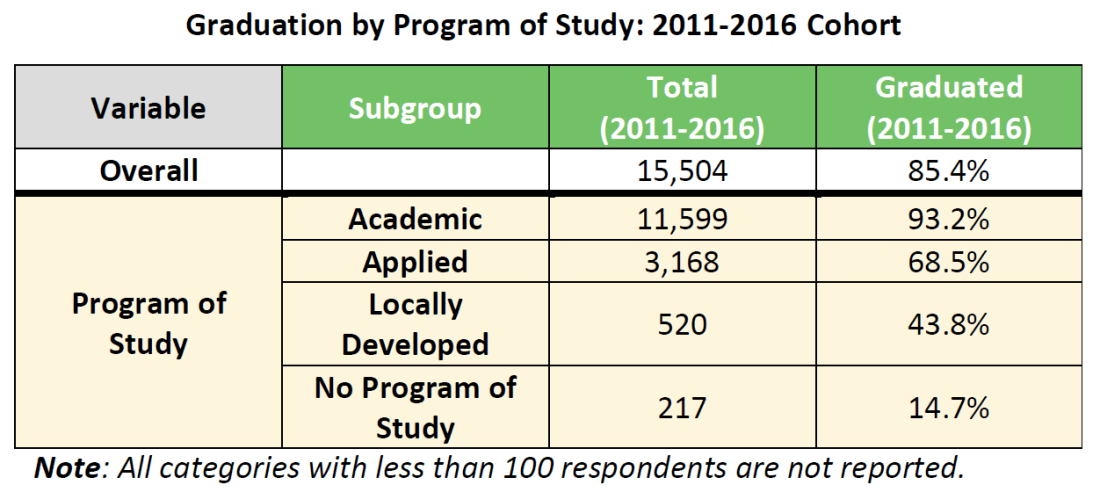

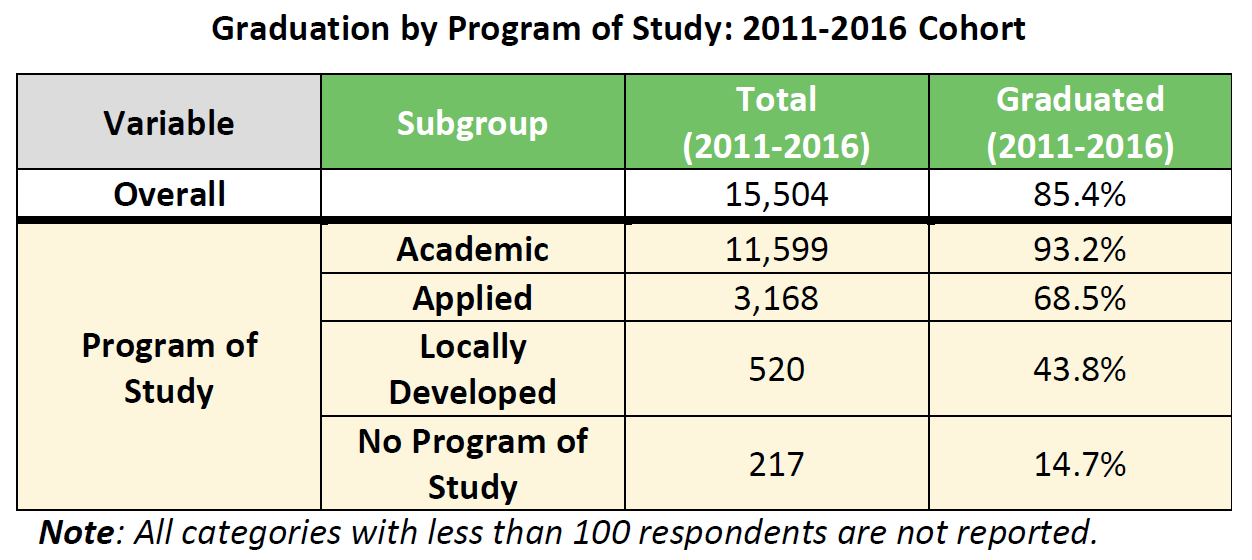

Academic streaming is the process of separating students into distinct educational pathways based on perceived ability. Since 1999, Grade 9 students have been placed in either the Academic or Applied course stream. Academic courses in Grades 9 and 10 serve as prerequisites and a foundation for university-preparation and college-preparation courses in Grades 11 and 12. Applied courses, however, generally only serve as prerequisites for college-preparation courses and Workplace options in the senior grades.

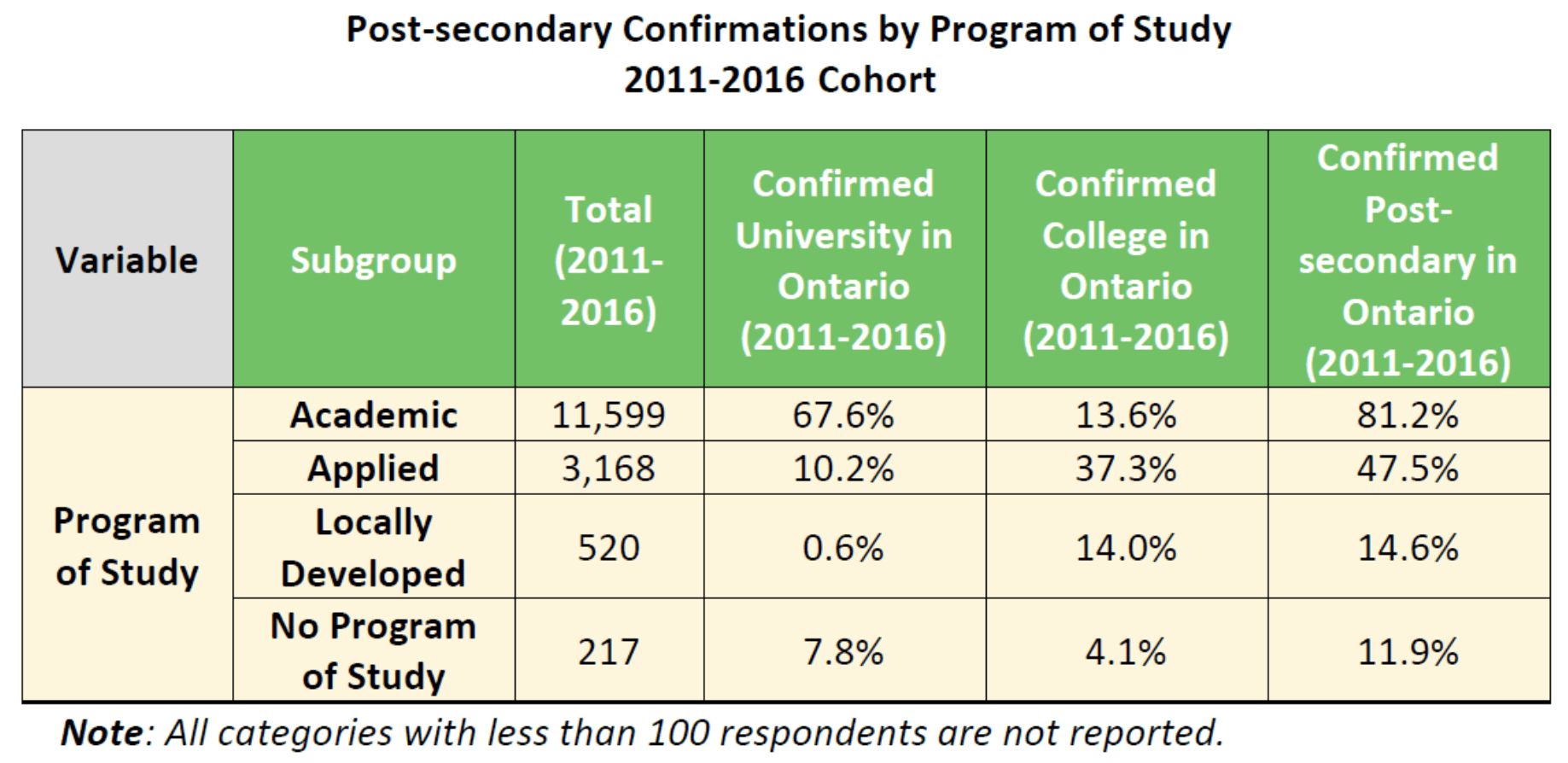

Therefore, Academic courses provide students with pathways towards all post-secondary educational destinations (i.e., university, college, or apprenticeship), whereas Applied courses prepare students for college, apprenticeship and workplace programs but courses do not qualify for university entrance.

TDSB is a leader in equitable and inclusive education, specifically in regards to investigating the impact of academic streaming. From 2013 to 2017, numerous reports were published that identified key effects of academic streaming. Structured Pathways (Parekh, 2013), showed that enrollment in Applied courses was associated with poorer academic achievement, higher suspension rates, higher dropout rates, and lower rates of acceptance to post-secondary education compared to enrollment in Academic courses. In addition, this report illustrated that students who are Black and Indigenous, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and students with special education needs were disproportionately placed in Applied courses.

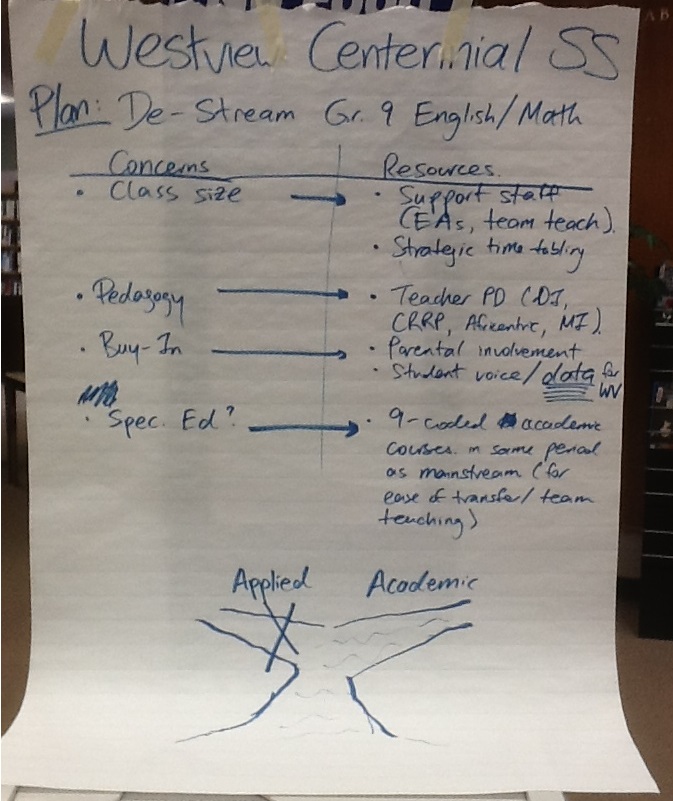

Sifting, Sorting and Selecting (TDSB, 2015), utilised these data profiles to create a working document and a series of professional learning sessions to school administrators and teacher leaders from four secondary schools and three elementary feeder schools in neighbourhoods with high numbers of Black families and with low socioeconomic status. It culminated with staff voluntarily committing to “destream” in at least one Grade 9 subject by eliminating the Applied course option and running “Academic-only” programming. Results after the first year indicated gains in academic achievement through measures including report card mark averages and achievement on EQAO assessments.

The success and impact of Sifting, Sorting & Selecting led to the creation of a similar series in 2017, titled Restructured Pathways, that expanded participation to 16 secondary schools and 47 elementary schools. In addition to examining streaming in secondary schools, elementary staff focused on the Home School Program (HSP) as a form of streaming. HSP was designed to support students with special education needs by providing a smaller class setting for at least 50% of the day for timed and tiered intervention., TDSB research found that students from racialized and low socioeconomic backgrounds were disproportionately placed in HSP and achieved lower academic outcomes.

Addressing academic streaming at a system-wide level was formalized through the adoption of the TDSB Multi-Year Strategic Plan (MYSP) in 2018. Goals within the MYSP included a review of the Home School Program and led to the phased elimination of HSP across the TDSB that was completed in 2022. Another goal in the MYSP was “to work over the course of three years to support the majority of students to study at the academic level for Grades 9 and 10.” Through a three-year phased approach, schools transitioned to providing Academic-only courses in Grades 9 and 10, culminating in the elimination of Grade 9 Applied courses in September 2021 and Grade 10 Applied courses in September 2022. During the transition period, extensive professional development on inclusive teaching was offered to teachers, curriculum leaders, and school administrators through departments including Academic Pathways K-12, English/Literacy, and Mathematics/Numeracy.

In its own efforts to address systemic discrimination in Ontario education, the Ministry of Education began destreaming Grade 9 courses across the province through the development of new curricula. Grade 9 Mathematics was the first course to be destreamed in 2021, followed by Science in 2022, English in 2023, and Geography in 2024.

Key Goals of Destreaming in TDSB

The three key goals of destreaming through Academic Pathways K-12 in the TDSB are the following:

- Increasing academic achievement for all students, particularly for those from historically and currently underserved groups, by elevating expectations, strengthening instructional practices, and providing appropriate supports and resources.

- Increasing students’ sense of belonging and engagement in inclusive and supportive classroom environments.

- Reducing, and ultimately eliminating, disparities in acceptance rates to post-secondary education by race, socioeconomic backgrounds, and special education status.

These goals are addressed in the action plan and associated timelines.

Destreaming in Grades 9 and 10

An important first step in secondary school to meet each of the goals above involves ensuring that students begin and continue to take Academic or destreamed courses. As of 2022-2023, almost all Grade 9 and 10 students are enrolled in the academic streams. From 2018-2019 to 2022-2023, there was significant growth in the proportion of students enrolling in Grade 9 Academic courses as the phased approach to destreaming was progressing.

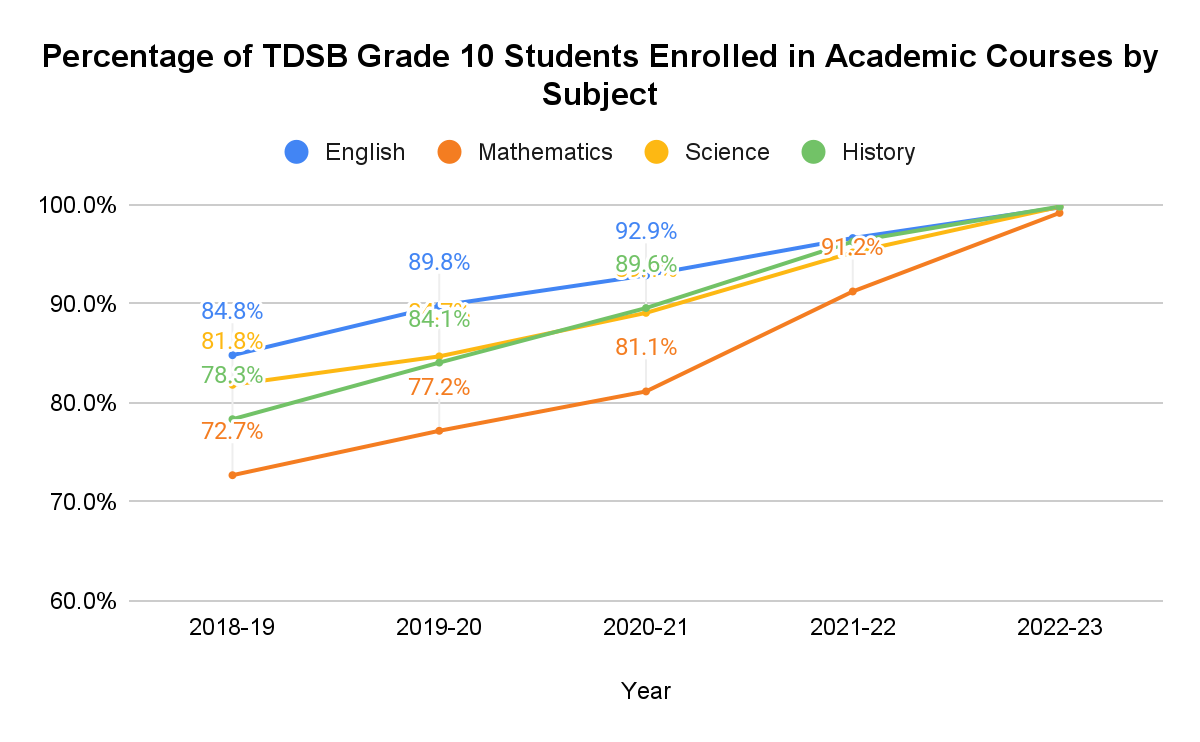

Currently, almost all Grade 9 students in the TDSB are enrolled in either Academic (English and Geography) or destreamed (Mathematics and Science ) courses (see Figure 1). In September 2023, the new destreamed Grade 9 English course was offered, and in September 2024, Grade 9 Geography will be a destreamed course. A similar trend occurred for Grade 10 Academic course enrollment, culminating in almost all TDSB students enrolling in Academic courses in English, History, Mathematics, and Science in the 2022-2023 school year (see Figure 2), which serve as prerequisites for university-preparation courses in Grade 11.

Figure 1: Percentage of TDSB Grade 9 Students Enrolled in Academic or Destreamed Courses by Subject (2018-2019 to 2022-2023).

Figure 2: Percentage of TDSB Grade 10 Students Enrolled in Academic Courses by Subject (2018-2019 to 2022-2023).

The student data that follows below maps out key success indicators in relation to student trajectories into post-secondary education opportunities. Successful transitions from Grade 8 into a Grade 9 is critical to establishing a successful trajectory for students into their later secondary education experience. The slides below begin with a breakdown of student enrollment in destreamed courses in Grade 9 and follow with enrollment in University Level course participation in Grades 11 and 12. These two stages for secondary school students are important to monitor as they provide insights into the likelihood of successful transitions of TDSB students into post-secondary education. In early secondary school, Grade 9, schools and

system leaders need to monitor the successful transition of students within the destreamed learning environment that almost all students are now engaged.

Achieving an average of 70% and above for the four academic core subjects—Geography, Science, English, and Mathematics—is a critical threshold for students in providing an academic foundation for successful participation in Grade 11-12 learning experiences (Figures 3) that in turn serve as a critical platform for postsecondary education access—both college and university.

Figure 3. Relationship between Grades 11-12 University Level Course Participation and Post-Secondary Education Opportunities (2005-2012)

Enrollment in Grades 11 and 12 University-Preparation Courses to Support Entry and Success in College or University

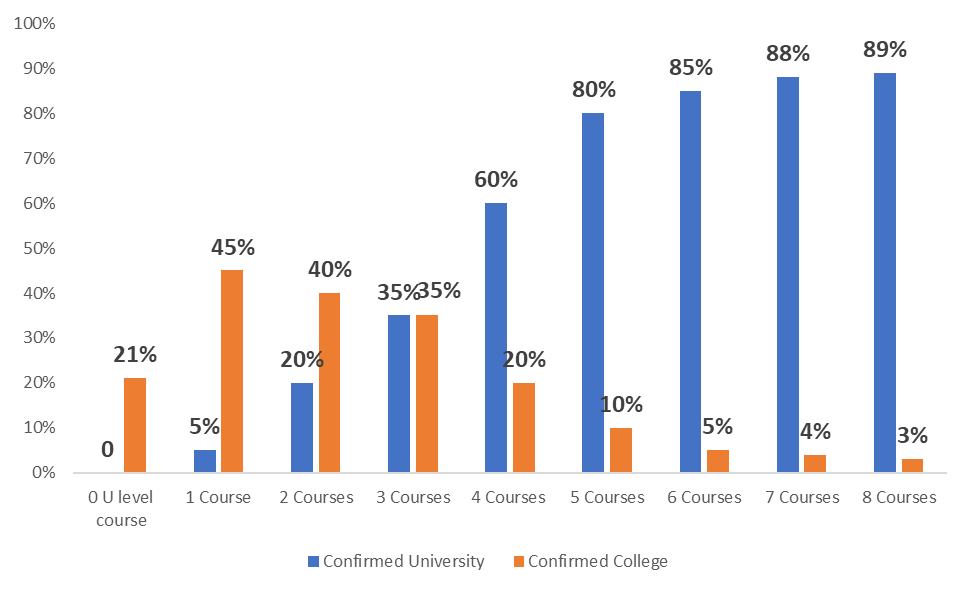

Increased student enrollment in university-preparation courses in Grades 11 and 12 is an important indicator that more students are prepared to enter, and succeed in, post-secondary education in college or university. Recent research has shown that among students who confirmed entry to an Ontario university within two years of graduating from secondary school, 99.8% of them completed Grade 12 university-preparation English. Also, a majority of students who confirmed entry to an Ontario college (53.0%) also completed Grade 12 university preparation English (Gallagher-Mackay et al., 2023). In mathematics, almost all students (98-100%) entering STEM and business programs have at least one Grade 12 university-preparation Mathematics course, in addition to a majority of Arts, Humanities and Social Science students (58%) (Brown, Parekh & Gallagher-Mackay, 2018). Students who take first-year college mathematics courses having completed university-preparation mathematics courses in secondary school outperformed those who completed college-preparation mathematics courses (Orpwood et al., 2012). TDSB Research has followed 129,000 students in cohorts from 2005-2012 in order to ascertain the relationship between University Level course participation in Grades 11-12 and postsecondary education opportunities of any kind. Only 21% of students who did not take one University Level course went on to any post-secondary education opportunity. However, 70% of students who took 3 university level courses of any kind went on to a post-secondary education opportunity, half of which was a college opportunity and half a university postsecondary opportunity (Figure 2).

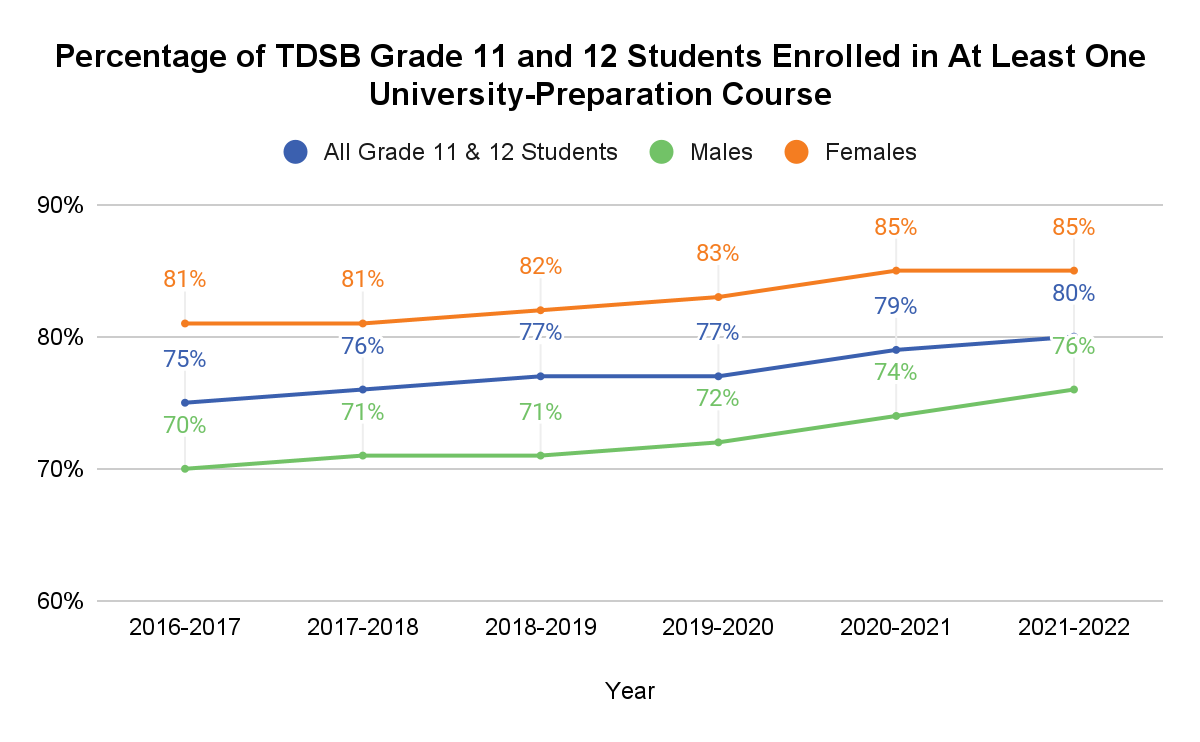

Due in large part to the destreaming efforts in the TDSB since 2015, the proportion of students enrolling in university-preparation courses has been increasing. Overall, the percentage of Grade 11 and 12 students enrolling in at least one university-preparation course has increased from 75% to 80% from 2016-2017 to 2021-2022 (see Figure 4). Historically, males were overrepresented in Applied courses (Parekh, 2013), which accounts for the disparity between males and females enrolled in university-preparation courses. However, that disparity has been decreasing over time, from 11% to 9%.

Figure 4: Percentage of TDSB Grade 11 and 12 Students Enrolled in At Least One University-Preparation Course (2018-2019 to 2022-2023).

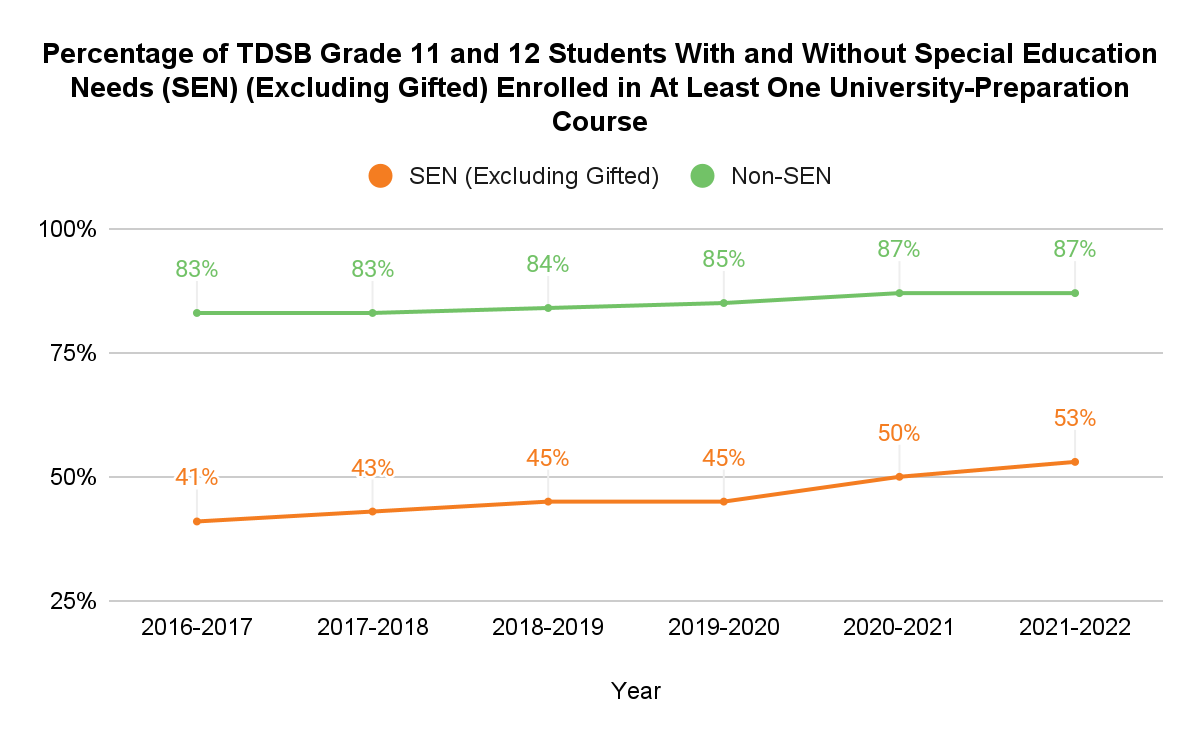

Students with special education needs (SEN) (excluding gifted) have seen large gains in university-preparation course participation during the board’s destreaming efforts. From 2016-2017 to 2021-2022, there was a 12% increase in students with SEN enrolling in at least one university-preparation course, compared to a 4% increase in enrollment for students without SEN (see Figure 5). While the disparity remains large, this is a promising trend that indicates destreaming efforts as having the desired effect of providing greater equity in educational outcomes.

Figure 5: Percentage of TDSB Grade 11 and 12 Students With and Without Special Education Needs (SEN) (Excluding Gifted) Enrolled in At Least One University-Preparation Course (2018-2019 to 2022-2023).

Increases in the rates of university-preparation course enrollment were measured across all self-identified racial groups in the TDSB. However, some groups experienced greater gains than others. Southeast Asian (15%), Middle Eastern (10%), Mixed (7%), and Black (7%) students saw the greatest increases in university-preparation course participation from 2016-2017 to 2021-2022 (see Table 1). Indigenous students, however, saw the least growth (2%) amongst self-identified racial groups and remain the group with the lowest rate of university-preparation course enrollment, indicating a clear area of focus for concerted improvement efforts.

Table 1: Percentage of TDSB Grade 11 and 12 Students by Self-Identified Race Enrolled in At Least One University-Preparation Course.

| Year | Black | East Asian | Indigenous | Latina/o/x | Middle Eastern | Mixed | South Asian | Southeast Asian | White |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016-17 | 60% | 90% | 37% | 63% | 72% | 75% | 86% | 67% | 82% |

| 2017-18 | 62% | 91% | 37% | 63% | 74% | 78% | 87% | 71% | 83% |

| 2018-19 | 64% | 92% | 38% | 66% | 76% | 78% | 87% | 72% | 85% |

| 2019-20 | 62% | 93% | 36% | 68% | 77% | 77% | 87% | 73% | 85% |

| 2020-21 | 63% | 94% | 34% | 66% | 82% | 79% | 89% | 78% | 86% |

| 2021-22 | 67% | 95% | 39% | 69% | 82% | 82% | 90% | 82% | 87% |

| 6-year change | +7% | +5% | +2% | +6% | +10% | +7% | +4% | +15% | +5% |

Applying and Attending College or University

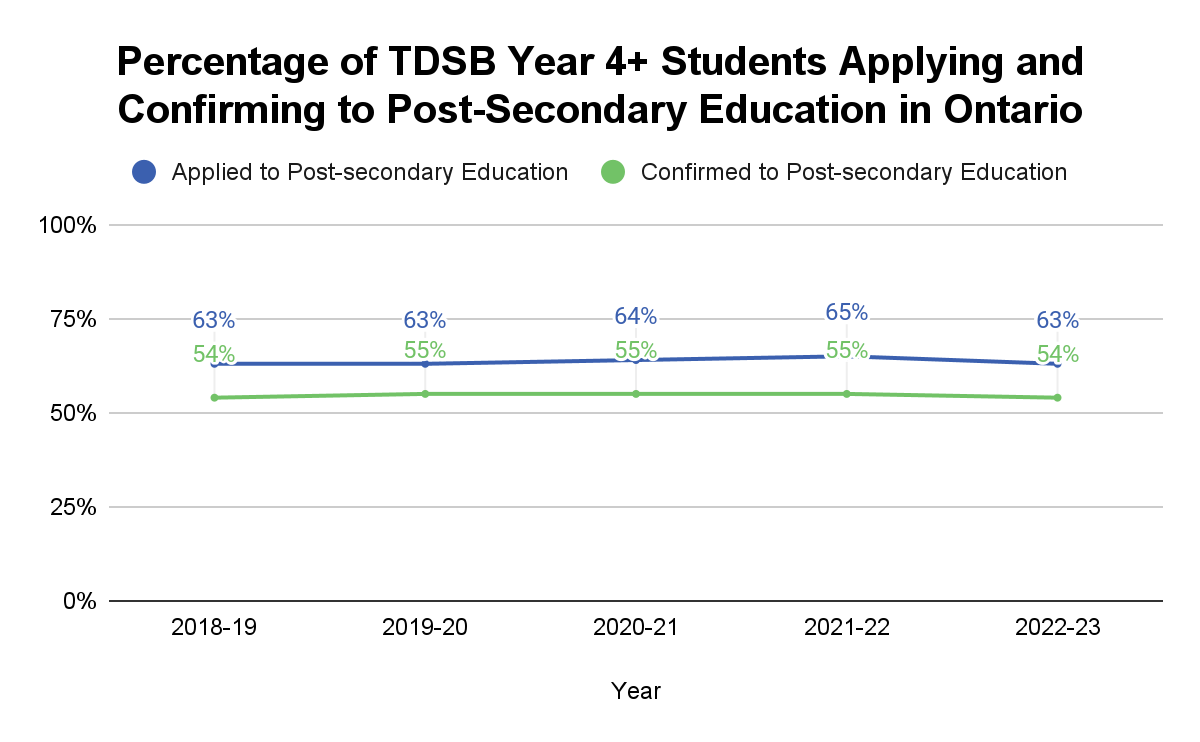

Despite clear growth in student participation in university-level preparation courses, there has not yet been a subsequent increase in applications and confirmations to post-secondary education. Rates of applications and confirmations to Ontario colleges and universities have remained steady (63% and 54%, respectively) from 2018-2019 to 2022-2023 (see Figure 6). The identification and elimination of possible financial, informational, societal, or systemic barriers to applying for postsecondary education is needed to increase these rates.

Figure 6: Percentage of TDSB Year 4+ Students Applying and Confirming to PostSecondary Education in Ontario (College or University).

Current Actions to Support Destreaming in TDSB at the System Level

As stated, the goal of Academic Pathways K-12 is to identify, address, and eliminate systemic barriers, eliminate disproportionate outcomes for historically and currently underserved students, while also enhancing inclusive instruction so that every student reaches the post-secondary destination of their choice. This commitment begins at Kindergarten registration to Grade 8, where students learn foundational skills and concepts that set them up for success in Grade 9 and 10 destreamed courses. In turn, those courses can lead students to university-preparation courses in Grades 11 and 12, which not only serve as prerequisites for university programs, but also provide the most robust preparation for college programs.

Professional Learning

Focusing on destreaming and inclusion to enhance learning from Kindergarten to Grade 12 requires educators to challenge historical notions of (dis)ability, race and other areas of bias, and reconceptualize how we serve students with varying skills and readiness. Numerous program departments in the TDSB, including the Academic Pathways K-12 department, have engaged educators in professional learning to address these needs. Expectations of staff for serving historically and currently underserved students are being raised to ensure that all students receive the support and opportunities they need to succeed. By providing ongoing professional development, the TDSB aims to equip teachers with the skills and knowledge necessary to create inclusive learning environments that meet the diverse needs of all students, and bring forward a more equitable and supportive system.

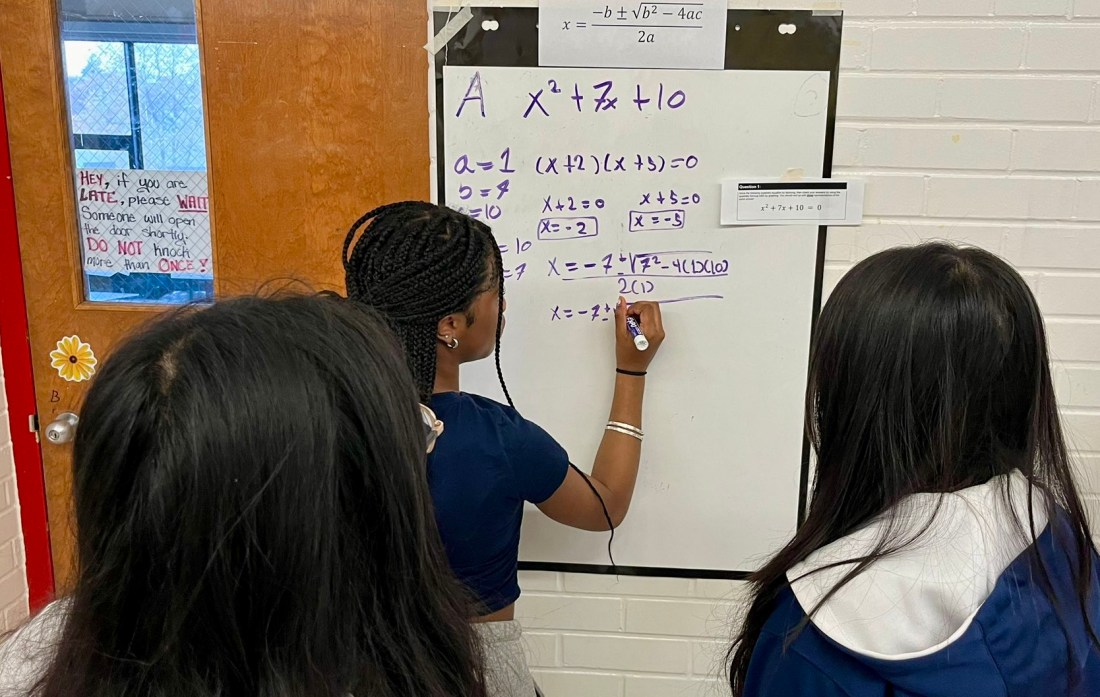

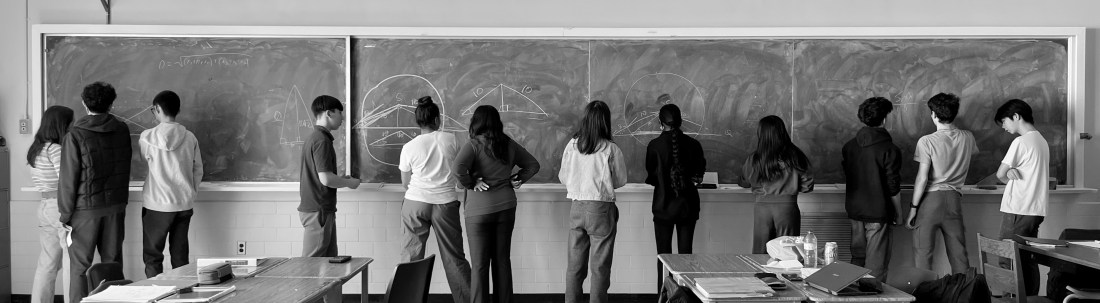

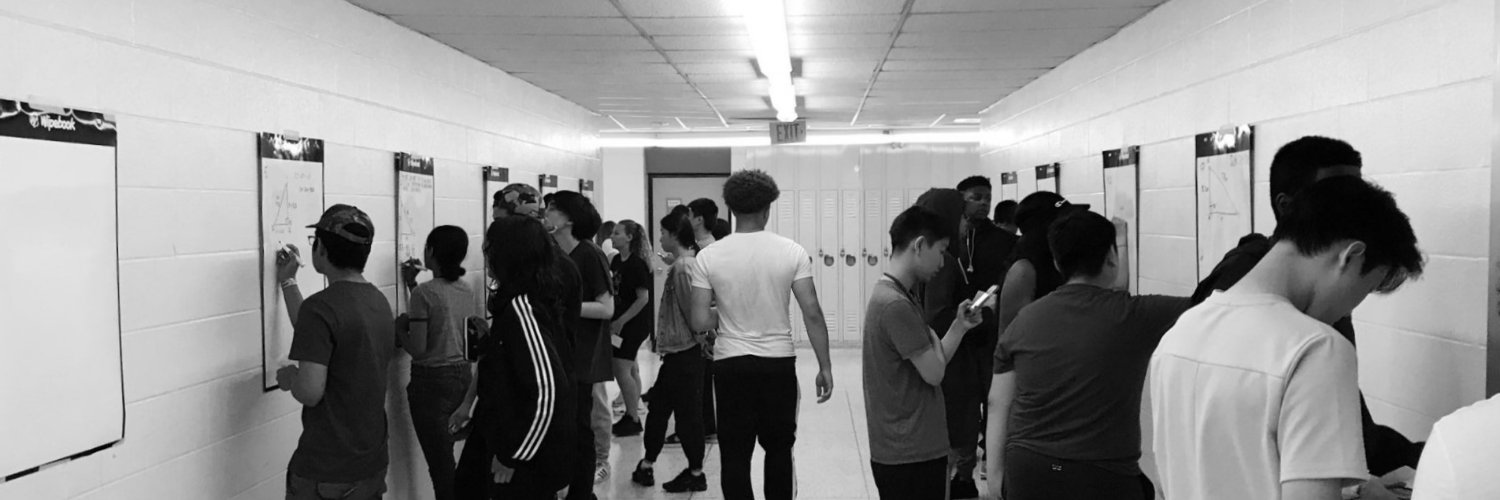

The Academic Pathways K-12 Department facilitated professional learning to over 300 Grades 7 and 8 teachers in January 2024 to support inclusive instruction in language and mathematics, as well as through the use of digital tools. Subject area departments have also provided hands-on workshops to teachers to deepen their practice in delivering the new Grade 9 destreamed English and the Grade 9 destreamed Mathematics course. In December 2023, a learning session for mathematics Assistant Curriculum and Curriculum Leaders (ACLs and CLs) from every secondary school focused on effective instruction and assessment for Grades 9 and 10 mathematics courses. As part of the Mathematics Achievement Action Plan, Math Learning Partners have provided in-depth professional learning to over 1300 K-12 teachers and administrators on effective and inclusive Mathematics instruction. This year, the Mathematics and Numeracy Department is offering a professional learning opportunity in partnership with OISE/UT to complement the work with Math Learning Partners called Destreaming Grade 9 Mathematics: Exploring the Curriculum through Inclusion, High Expectations and Impactful Practice. This multi-day learning will occur throughout the 2024-25 school year. Math Learning Partners have worked and will continue to work alongside Grades 3, 6, and 9 mathematics teachers in classrooms to assist with implementing high-impact instructional practices and teaching the mathematics curriculum with fidelity.

Teaching Resources

The TDSB is committed to ensuring that all schools have adequate resources to meet the diverse needs of learners. These resources are culturally relevant and responsive, and demonstrate academic rigor and high expectations for all students. Classroom-ready teaching resources have been provided to teachers to complement their professional learning. For example, the English/Literacy department has provided sample lessons as part of the Grade 9/10 support plan and shared the TDSB Literacy Success Diagnostic Kits with secondary English teachers. In mathematics, teachers in Math Learning Partnership schools have access to digital teaching resources (MathUP and Mathology). All Grade 9 mathematics teachers in the TDSB have access to MathUP, a Ministry-approved resource to use in destreamed classes, and online tools including Knowledgehook and Brainingcamp to augment classroom learning.

Additional Staff

The Ministry of Education provided $11.2 million for additional staff to support destreaming and the transition to secondary school for the 2023-2024 school year. These funds were used to staff elementary guidance positions, reduce class sizes in Grade 9 , provide in-class support for students, and create in-school destreaming coaches to build staff capacity in inclusive teaching and learning.

One challenge that the TDSB will face for the 2024-2025 school year is the removal of the $11.2 million funding from the Ministry of Education to support destreaming and the transition to secondary school. This funding reduction in staff allocation may hinder the board’s ability to effectively implement programs aimed at academic programming and support historically underserved students. Without this financial support, the TDSB will need to attempt to find alternative resources or strategies to continue providing essential services and support for students during these critical educational transitions.

Student Tutoring and Mentoring Program

For the past three years, the Academic Pathways K-12 Department has facilitated a student tutoring and mentoring program, where paid senior students support Grades 9 and 10 students in English, mathematics, science, geography, and history. From September 2023 to May 2024, 19 secondary schools have provided over 2500 hours of tutoring to strengthen achievement in destreamed and Academic courses.

Academic Pathways K-12 Strategy 2024-2028: Action Plan and Associated Timeline

The following goals and actions aim to guide students and provide the necessary support and resources for them to succeed in various post-secondary pathways, whether that be college, university, apprenticeships or directly entering the workforce.

Action: Enhance Teaching of Foundational Skills in Literacy and Numeracy from Kindergarten to Grade 8, and Reduce the Number and Severity of Curriculum Modifications in Literacy and Numeracy in Grades 4-8

The goal is to have students move from their modified grade level in language and mathematics to their age-appropriate grade level. This will be accomplished by supporting the acquisition of foundational literacy and mathematics skills in children which is at the heart of addressing academic streaming and setting students up for success throughout their K-12 educational experience. The Academic Pathways K-12 department will coordinate with the English/Literacy, Mathematics and Numeracy and Special Education and Inclusion departments to support the offering of professional learning opportunities to K-8 educators that lead to the effective implementation of evidence-based instructional strategies for developing foundational literacy and numeracy skills, taught within meaningful and culturally relevant contexts.

For students who have been historically and currently underserved and have curricular expectations modified to a lower grade level on their individual education plans, having a concrete plan for accelerating learning so that they reach grade-level expectations alongside their peers is vital to effective inclusion. We will provide professional learning to elementary staff to illustrate promising teaching practices that accelerate language and mathematics learning for students.

Key Monitoring: In partnership with the Research department, Special Education and Families of Schools, we will monitor the number and severity of curriculum modification over time.

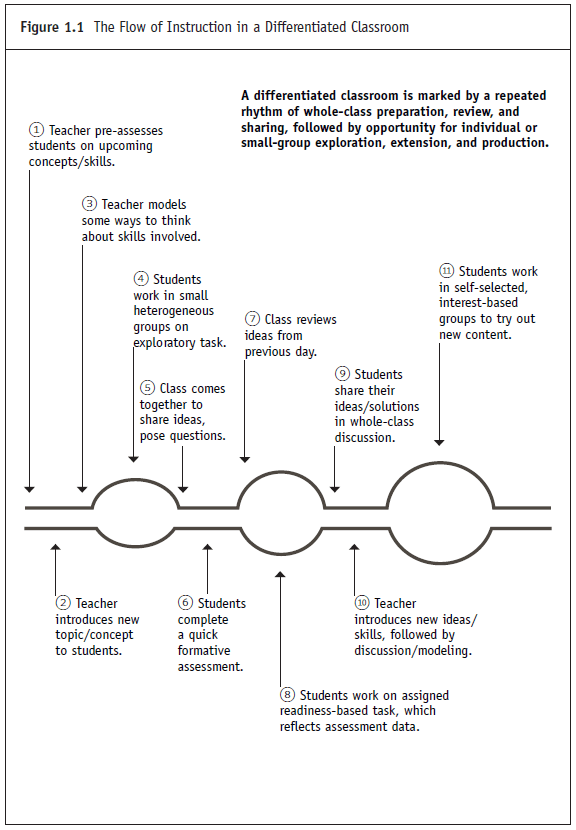

Action: Support Academic Achievement in Grades 9 and 10

TDSB research has indicated that not only are the earning of credits important, but the quality of the credits matter as well. That is, a student who achieves at or above the provincial standard in Grades 9 and 10 is more likely to achieve success in future grades compared to those that do not. Therefore, ongoing professional learning for staff teaching Grades 9 and 10 courses must continue in order to enhance academic achievement. The professional learning sessions that will be offered in collaboration with individual subject-area departments, will promote the effective use of evidence-based instructional practices, including differentiated instruction, universal design for learning, and culturally relevant and responsive pedagogy.

Key Monitoring: Achievement levels for Grade 9 destreamed and Grade 10 Academic courses will continue to be monitored. Monitoring will be expanded to include students’ sense of belonging and engagement.

Action: Provide Adequate Resources to Meet the Diverse Learning Needs of Learners

The implementation of teaching practices that are culturally relevant and responsive in order to support effective instruction can be enhanced and accelerated by providing staff with appropriate teaching and learning resources. The department will work with various subject-area departments to determine how best to utilize the Ministry’s De-streaming Implementation Supports program to maximize impact on students and teachers.

Key Monitoring: The department, in partnership with the Family of Schools, and subject-area departments will monitor well-being, belonging, engagement, and achievement levels using various measurement tools to assess how effectively the supports have helped students. By tracking these key indicators, we aim to provide the initiatives that are making a positive impact on students’ overall educational experience and outcomes.

Action: Increase Proportion of First Nations, Metis and Inuit Students Participating in University-Preparation Courses in Grades 11 and 12

The Academic Pathways K-12 department will work in partnership with the Urban Indigenous Education Centre (UIEC) to increase the proportion of First Nations, Metis and Inuit students participating in university-preparation courses in Grades 11 and 12 over the course of the next three years.

Key Monitoring: In partnership with the Research department and the UIEC, ongoing data will be collected to indicate the proportion of First Nations, Metis and Inuit students participating in university preparation courses.

Action: Increase Proportion of Black Students Participating in University-Preparation Courses in Grades 11 and 12 and Pathways to Postsecondary Education

The Academic Pathways K-12 department will work in partnership with the Centre of Excellence for Black Student Achievement to increase the proportion of African, Afro-Canadian and Black students participating in university-preparation courses in Grades 11 and 12 over the course of the next four years. This partnership will support students in identifying diverse post secondary pathways.

Action: Increase Level of Application to Post-secondary Education

The Academic Pathways K-12 department will work in partnership with the Guidance, Career Development & Student Well-Being department and graduation coaches to determine and address barriers for students to apply to post-secondary education.

Key Monitoring: In partnership with the Family of Schools, Guidance, Career Development & Students Well-Being department, Research department and the Equity team we will monitor student experience and trajectories to provide opportunities for students to post-secondary education.

References

Brown, R., Parekh, G., & Gallagher-Mackay, K. (2018). Getting Through Secondary School: The Example of Mathematics in Recent TDSB Grade 9 Cohorts. Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO) 2018 Annual Conference Pre-Conference on the Tri-Ministry Ensuring Equitable Access to Postsecondary Education Strategy (Access Strategy).

Gallagher-Mackay, K., Brown, R.S., Parekh, G., James C.E. & Corso, C. (2023). “I have all my credits – now what?”: Disparities in postsecondary transitions, invisible gatekeeping and inequitable access to rigorous upper year curriculum in Toronto, Ontario. Toronto: Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community and the Diaspora at York University.

Orpwood, G., Schollen, L., Leek, G., Marinelli-Henriques, P. & Assiri, H. (2012). College Mathematics Project 2011: Final Report for the Ontario Ministry of Education and the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities. Toronto: Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology

Parekh, G. (2013). Structured Pathways: An Exploration of Programs of Study, School-wide and In-school Programs, as well as Promotion and Transference across Secondary Schools in the Toronto District School Board. Toronto: Toronto District School Board.