short·cut (noun \ˈshȯrt-ˌkət also -ˈkət\): a method or means of doing something more directly and quickly than and often not so thoroughly as by ordinary procedure (via merriam-webster.com).

Who doesn’t love a good shortcut? If you use them, you get places faster, get more things done, or do something at a fraction of the time. But, as the above definition suggests, shortcuts are often not as good as the original thing. Unfortunately, with respect to mathematical procedures, the same holds true. I’m personally a math teacher who’s big on teaching for understanding rather than simply to be proficient, and so I never EVER show my students the “shortcuts” that work but don’t follow any mathematical principles. Sure, they do the job okay, but I feel that they come at the expense of students understanding and/or consolidating mathematical rules. Besides, a few of these shortcuts don’t actually save any time, steps, or pencil lead anyway, so why do they persist? My guess is because teachers today were taught the same shortcuts when they were students back in the day, and so we teachers perpetuate the same ill-advised methods to the next generation because, well, they work.

There are two such shortcuts I have identified (though definitely not the first person to do so) that I am on a mission to remove from the face of the Earth. I will show definitively that the more mathematically-sound procedure is actually just as fast, if not faster, than the traditional shortcut. Note: don’t worry if you’re not a math whiz – chances are you’ve been taught these shortcuts before so some of this will ring a bell.

Bad Shortcut #1: Solving equations by moving terms to the other side of the equation (i.e. the Magic Portal Method)

So, the premise is this: to solve a linear equation, such as 3x + 7 = 22, you would first need to remove the 7 from the left side of the equation in an effort to isolate the variable, x. How have most students (including I) been taught to do this? Well, we simply move the +7 to the other side of the equation and change the sign so that it’s now -7. But here’s the issue: why does the sign get to change when a term moves to the other side of an equation? Is the equal sign a gateway to some sort of magic portal that transforms positives to negatives, goodness to evil, or Rob Ford to a respectable political figure? Of course not. There is no justification for changing signs. This is a shortcut without a mathematical leg on which to stand, and yet it is so widely popular (strangely, I can’t find a consistent name for this shortcut, so I’ll refer to it from now on as the Magic Portal Method – trademark). Yes the method works, but when you really think about it, it actually doesn’t make any sense! Why not do something that DOES make sense?

Solution to Bad Shortcut #1: the Balanced Method

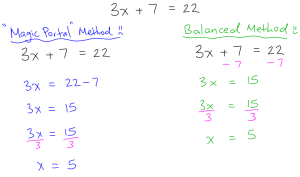

As a recap, equations are math statements with two sides showing that two expressions are equal. If one side of an equation is altered, the same change must be made to the other side in order for the expressions to remain equal. If 5 is added to one side of an equation, then 5 must be added to the other side in order for the balance to be maintained. This is the essence of solving equations using the Balanced Method. The mantra that I chant with my students is: “Whatever you do to one side of an equation, you do the same thing to the other side,” which is mathematically valid. Terms are removed from an equation by performing inverse operations (i.e. doing opposite things). In other words, we undo whatever is happening in an equation. To show how the Balanced Method compares to the Magic Portal Method, here are the solutions to solving 3x + 7 = 22 using both approaches:

Using the Balanced Method, the first step is to remove the +7 by subtracting 7 on both sides of the equation. When comparing to the Magic Portal Method, the Balanced Method actually one fewer step AND makes sense mathematically. You get to have your cake and eat it too.

What if there are variables on both sides of the equation? Let’s see:

As you can see, the Balanced Method uses the same number of steps as the “shortcut.” Also, note that in the solution using the shortcut, the Balanced Method is actually utilized at the end (dividing both sides by 2). Why should we use two different strategies when one will suffice?

Whenever students share with me that they have learned to solve equations by moving terms to the other side and switching signs, I ask them why they are allowed to do that. Their most common response: “Uhhh…just ’cause.” We math teachers are not doing students favours by promoting nonsensical tricks that don’t actually help with making life easier. If the Magic Portal Method isn’t really a shortcut AND it doesn’t make sense mathematically, then maybe we as math teachers should reconsider sharing it with our students and instead focus on the more mathematically-favourable Balanced Method as a way to solve equations.

Bad Shortcut #2: Solve a proportion by cross-multiplying

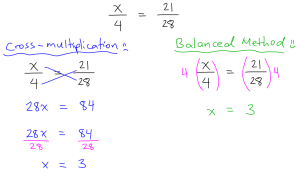

Okay, so this is also technically solving equations, but when two fractions are equated, such as x/4 = 21/28, we’ve been historically taught to use another little trick to solve buggers like this: cross-multiplication. Simply put, the first step to cross-multiplication is to multiply the numerator of one fraction with the denominator of the other fraction and make the products equal. Similar to moving terms to the other side of an equation, this procedure is also without merit. Again, this method works, but math students typically do not know why they can do it, and that’s the main problem. Let’s contrast the cross-multiplication solution to x/4 = 21/28 with one using the Balanced Method:

Well, this is embarrassing. It seems that the Balanced Method provides the Usain Bolt of solutions, while the cross-multiplication solution is more like an injured mule. Clearly, the shortcut is the long-cut here. You may wonder how the Balanced Method can be used if the variable is in the denominator rather than in the numerator. All you would have to do is take the reciprocal of both sides to fix that issue (i.e. flip both fractions upside-down):

Same number of steps. Short-cut, shmort-cut.

So there you have it. It appears that moving terms to the other side of an equation and cross-multiplication are techniques that not only students use without any understanding, but they also don’t even make math any quicker. By instead focusing on the universal approach of the Balanced Method, math teachers can promote a sound understanding and a better way to solve equations. Let’s not share the poor methods of our forefathers and break the cycle of ineffective math skills.

Below are a few advantages of the Transposing Method (shortcut);

1. It can perform many solving steps in just one step, without having to perform double-writing of terms on both sides.

Exp: Solve 5x – p + q – r + 7 = 2x – s + t + 8 – 9 (10 terms before move)

5x – 2x = -s + t + p – q + r + 8 – 9 – 7.(10 terms after move)

3x = (-s + t + p – q + r – 8)

2. It can easily check the overall transition of terms by observing the simple Rule: “No missing terms, no new terms added, after every move”.

3. It allows smart moves by switching around numerator to denominator, and vice versa.

Example: Solve (m – 3)/(n + 4) = (p + 2)(x – 1).

Move (x – 1) to left side and other terms to right side.

(x – 1) = [(p + 2)(n + 4)]/(m – 3).

4. It will greatly help, when students later have to deal with more complicated equations and inequalities in higher math studies. They don’t have to perform double-writing of terms in every solving step, that wastes time and that is usually main causes for errors/mistakes

5. It always keeps the equation balanced (see proofs in many articles post on Google, Yahoo). It doesn’t divide solving linear equations in many steps that complicates the solving process.

I understand that shortcuts have the intention of making things simpler and speeding up an otherwise slow process. However, when students begin to learn how to solve an equation, they need to understand that equations represent a balance and equality between the two sides.

The examples that you’ve provided work, of course, but why those “movements” of terms are mathematically valid cannot be explained without first having an understanding of the balanced approach.

I have no qualms about students using shortcuts, so long at they can explain why they work. If they don’t get that, then they miss why we do math. It’s not rote memory and procedural efficiency that’s valued (at least for me). It’s about having a deep understanding about how numbers relate and what we can do with those relationships to solve meaningful problems. To skip a conceptual understanding of math for the sake of doing things faster, to me, does students a great disservice.

I agree with of these statements as dislikes. If students learn to balance equations, they can balance more than one thing at a time so really it is always just as fast and gives more meaning. Saves the problem of 3 – x = 2, whwen students alwasys want to add 3 to both sides because of subtraction in front of x. Also, cross multiplying!!! Why do we have a different rule when we call it a proportion than we do if it is just an equation? Is a proportion an equation?

1. Adding artificial steps to methods you don’t like does not support your position that the methods “don’t save steps”..

3x+7=22

Step 1: 3x=15

Step 2: x=5

(2 steps, not the 5 you show)

4x+5 = 2x-7

Step 1: 2x = -12

Step 2: x= -6

(2 steps, not 4)

6/x = 15/10

Step 1: 60/15 = x

Step 2: x=4

(2 steps, not 3)

2. You say these rules “make no sense”. As a teacher they should make sense to you. A rule of algebra is valid when it keeps an equation balanced. Subtracting a value from both sides of an equation keeps an equation balanced. Moving an additive term from one side of the equality to the other while changing its sign keeps an equation balanced. If you teach it from that perspective then it imparts every bit as much understanding about math as your long-winded methods. The problem is in teaching these methods as informal “shortcuts” rather than as primary approaches in their own right.

Respectfully yours,

I completely agree with *most* of what you’ve written, but I’d argue that taking reciprocals of a proportion when the variable is in the denominator requires a conceptual understanding of fractions that I often don’t see from students. Mind you, I think it should be taught, but if it isn’t taught, then taking reciprocals of both sides of an equation can seem like magic. I would teach the 6/x = 15/10 method using a few more steps:

6/x = 15/10

x(6/x)=x(15/10)

6=15x/10

10*(6) = 10* (15x/10)

60 = 15x

(60)/15 = (15x)/15

4 = x

Of course, once students are comfortable with the idea that a/b * b/a = 1, then I’d speed things along a bit:

6/x = 15/10

x(6/x)=x(15/10)

6=(15/10) x

(10/15)*(6) = (10/15)* (15/10) * x

60/15 = 1* x

4 = x

N. Nguyen:

1. In your point #1, you can “transpose” multiple terms in fewer steps but without resorting to magic, by using Jason’s “Balance” principle (formally, the Addition and Multiplication Properties of Equality) and “stacking” what you are adding or subtracting beneath a “like term” (another important math concept). There’s nothing to stop a mathematician from adding or subtracting more than one term in one step:

5x – p + q – r + 7 = 2x – s + t + 8 – 9

-2x + p – q + r – 7 = -2x -7 + p – q + r

__________________________________

3x = -s + t + 1 – 9 + p – q + r

= -s + t – 8 + p – q + r

x = (-s + t – 8 + p – q + r) / 3

2. In your #2, your “simple Rule” is not enough: you would also need to confirm that the sign of a term changes when you “transpose” it to the other side. It’s much simpler, IMO, to understand and apply “balance” principle.

3. In your #3, your partial solution to

(m – 3)/(n + 4) = (p + 2)(x – 1)

is incorrect. You wrote:

(x – 1) = [(p + 2)(n + 4)]/(m – 3)

This is exactly the kind of careless mistake that comes from shortcuts. If instead you use the Multiplication and Addition Properties of Equality, you get the correct answer, clearly and understandably:

(m – 3)/(n + 4) * [1 / (p + 2) = (p + 2)(x – 1) * [1 / (p + 2)]

(m – 3) / [(p + 2)(n + 4)] = x – 1

+ 1 = + 1

__________________________

(m – 3) / [(p + 2)(n + 4)] + 1 = x

About your #4 & #5: see #3 above.

In my experience teaching math in grades 5-11, those “extra” steps are not “artificial”. They are what justify (i.e. prove) the solution. Math is rigorous; it’s not just about getting an answer, it’s also about showing that your answer is correct, so that anyone who understands the principles & properties (e.g. properties of equality; commutative, associative & distributive properties) can clearly see the solution is correct. When my students tried skipping steps they often made mistakes. For example, instead of

6/x = 15/10

Step 1: 60/15 = x

Step 2: x=4

They might do:

Step 1: x = 6*15/10

Step 2: x=9

New York State’s Regents exams in high school math (Algebra 1, Geometry and Algebra 2) https://www.nysedregents.org/regents_math.html often specifically require students to justify their solution.

Agree. Taking the reciprocal is not by itself justified by properties of arithmetic. I think the “shortcut” of multiplying by the reciprocal 10/15 is justified by the Multiplication Property of Equality, so it’s still a perfectly rigorous solution.

Agreed, these are “shortcuts” to be avoided. I think students should first, understanding of principles; then, build comfort and accuracy in procedure; then speed.

In addition, I would name the property that justifies each step, including the Multiplication Property of Equality and the Addition Property of Equality — just as with a proof in Geometry.

1. New York State math tests ask for them.

2. Not every operation on both side preserves the solution set. Taking positive square root of both sides can “lose” a possible solution.

x^2 = 9

x = 3

Squaring both sides, or taking the absolute value of both sides, can generate extraneous solutions.

sqrt(x) = -3

x = 9